CJ SWEET

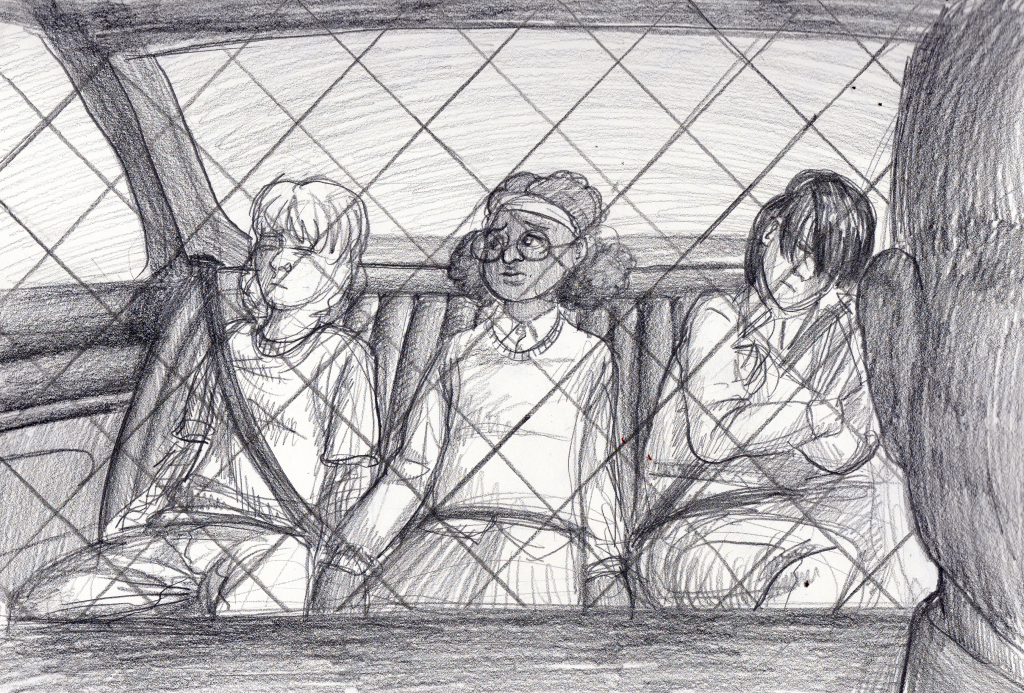

As the police car reached the end of the dirt road and turned onto Fell-Munch, CJ kept looking between Rick and Jay, and thinking about the situation of all three of them as they sat in the back of the police car.

Jay’s hands were lying limp at his sides. His eyes were closed. His head bobbed and swayed a little, from left to right, from the uneven movement of the car as they were driven along.

Of course, CJ knew that Jay wasn’t asleep, even though he looked like he was. She knew that Jay did that sometimes — went limp, when things got to be too much to handle for him; it was like he was trying to wait out a crisis by playing dead.

Rick had his head pressed up against the gated back-seat window. His long bangs were sweat-slicked and matted wildly. He, too, was silent — but his lips were moving just a little bit, like he were talking inaudibly to himself.

“Name’s Otis Falke, by the way,” the policeman who was driving them had told them just a few minutes after they gotten onto the main road. After that, though, it had been silence — or, mostly silence, anyway. Otis Falke kept on making a deep-inhalation sound every so often, followed by a quiet exhale — the way a lot of adults do when they’re trying to figure out how to broach a difficult subject or discuss something they don’t want to talk about with kids.

The silence was broken up every so often, though, as Otis’ police radio would belch out the sounds of static and of conversations going on between the people who were still up by the Marsh House. Once in a while, Otis would pick up his handset and update the other police about their progress on the road.

CJ had stopped paying attention to the radio after the first half-hour of driving. She quickly became inured to hearing her last name being spoken over and over in-between fits of static. There were facts to collect, of course — CJ hadn’t known Rick’s last name was Boyle until Otis identified his passengers; she’d always thought it was Leek — but the rest just seemed like busy noise. She was grateful for the lack of conversation between the car’s occupants, too. Pointlessness annoyed her to no end. The other children were lost in themselves, and she definitely didn’t need nor want whatever chatter Otis might have attempted. She could see his reflection in the interior rear-view mirror. Something about CJ’s middle position in the back seat was creating an optical illusion in the mirror that made Otis’ mouth look like it was doubled in the middle of his forehead. It unnerved CJ, and distracted her. She reasoned that maybe it was just the adrenaline wearing off, but she was shivering a little; she felt cold — even with the sunlight beaming into the back of the police car. It felt to CJ like the pale yellow sunlight was somehow cold; and, a part of her was glad for the cold. It meant she was getting away from the fires at the Marsh place. CJ shifted in her seat a little, turning her head to look out the back window. The woods were in the far distance, now, mostly out-of-sight. Behind them on either side of the road lay fields of thick weed. Here and there were some abandoned business fronts and the few closed factories close to town that hadn’t been renovated or torn down. Then, eventually, the closed factories started to give way to businesses that were still open. The better things looked along the side of the road, CJ knew, the closer they were to the center of town.

“Are we getting close yet?” Jay asked, his head still hanging down. He sounded so tired that it made CJ”s own feelings of exhaustion feel more pronounced.

CJ turned back toward the front window. “Just about,” she said, trying to make herself sound as calm as she could. Fitz Circle had come into view, and that meant they’d just about arrived at the police station. “Little ways more.” Meanwhile, CJ was thinking lawyers, and survival, and how serious their situation was. None of them had gotten their Miranda rights or anything formal read to them: they hadn’t been arrested. She thought about whether she or the others needed legal counsel. She wasn’t sure. She decided to wait it out before declaring she needed a lawyer. Doing that would put her in a suspicious light. It was the same for Jay. It was less so for Rick. With the police involved, things were precarious for the black kid and the disabled Native American kid. She was being careful not to talk except when it was necessary. She knew that, even without Miranda rights being read, what she said and did could – and maybe would – be used against her … if not by the cop in the front seat, then by someone else along the way. Cataloging the police in Drodden along the lines of their bigotry didn’t mean she could control which of them she ran into along the way. She tried to keep herself walking a tightrope of a calm appearance and a constant state of readiness. It was exhausting, but she kept it up as the car drove along.

The car turned onto the roundabout at the center of Drodden and quickly exited before turning to drive down into an underground parking lot. “And here we are,” Otis said, rather flatly, before shutting off the car and turning to look toward the passengers behind the grilled gate between them. “You can call me Otis, by the way.”

“Hey,” CJ said, working to keep her voice as noncommittal as possible.

“Hi, Otis,” Rick said, waving his left hand limply. Rick’s tone might have been sarcastic, if he’d put any force behind his voice.

Jay just sat there, his head still down.

Otis waited a while, looking toward Jay. When no response was forthcoming, he continued. “You guys ready to go upstairs? Sounds like your folks are all here.” Otis gestured over his shoulder toward the radio with his right hand.

CJ was surprised with herself. She hadn’t heard that news come from the radio. She figured that she’d sort of tuned out the radio chatter, and it pained her to realize she’d ignored critical environmental details. She felt disappointed in herself.

Falke got out of the car and opened the back door on Rick’s side. He knelt a little and looked in at the children. “You guys ok to walk over there?” he asked, gesturing toward a big elevator on the other side of the small underground garage.

CJ waited while Rick got out of the car, and then reached over to brush the back of her hand across Jay’s forearm. “Come on,” she said, sounding to her ears too unsympathetic. But she also knew that Jay wouldn’t respond to sympathy. Her beliefs were confirmed when Jay silently got out of the police car after her. She looked over to him to try to gauge him. She was having a little trouble with that, because of how Jay was hanging his head. She wondered if it was just the trauma of what they’d all experienced, or if he was having a reaction to taking his pills so much later in the day than he usually did. And she again criticized herself for letting the issue of Jay’s medication way as long as she had without considering it.

Otis pressed the call button for the elevator, and the doors opened to reveal that the car inside was just as worn-down as the rest of the Drodden police station. But it looked very clean; it smelled like lemons once the group was inside. The three children were silent as Otis pushed the button for the second floor. Then, the elevator doors shut and it shuddered upward. When the doors opened again, a mechanical-sounding voice — presumably meant to resemble a typical woman’s — announced “Second Floor” with the expected combination of unnatural pronunciation and odd emphases.

CJ had never been in the Drodden Police Station, and actually being in this environment surprised her a little bit. It had begun to strike her with the carpeted elevator; the four of them stepped out onto the likewise blue-carpeted floor of the main hall of the second floor. There was a crude map on the wall, next to a sign that read:

DRODDEN POLICE DEPARTMENT

TEMPORARY LAYOUT

YOU ARE HERE

There was a red arrow that pointed to the hall on the map where they all were, and different rooms were labeled about what they were for. CJ was struck by how quiet it was. Yes, there were people milling around and talking to each other — some in and some out of uniform — but there wasn’t the sort of urgency she’d expected. She was doubly disappointed with herself as she considered whether movies and television had projected a false sense of reality that had poisoned her perceptions a little. Her favorite TV show was a police procedural called Two Days, about a pair of brothers who worked in a police precinct in Washington. She knew it was fiction. She also knew it was total junk. But the actors who played Stephen and Michael Day did such a good job on the show that CJ never missed it. She found a mild sort of comfort in putting her thoughts on a different track — any different track, really — from what she’d seen at the Marsh house, even for just this moment. Her dad didn’t approve of her watching crime dramas. He said they were a frivolous waste of time. But CJ just flat-out didn’t care about that particular objection of her father’s. She liked watching the shows; she enjoyed trying to solve the crimes. She dealt with enough garbage in her life; she had to think about frivolous things every so often — to keep herself together. So, to try and relax just a little, she thought about Two Days, and how much she liked it. And how the writing was always really interesting – lots better than most cop shows on TV. She knew from reading magazine articles that the writers of Two Days often said they prided themselves on being accurate, but the constant chaos of the police station on the TV show was the opposite of the professional workplace in which CJ currently found herself. Everything around her was ordered. There were all these plastic folder-holders — many filled to capacity with papers, but neatly placed. The holders were tightly screwed into the walls at even intervals, each to the left of a windowless door. The doors had thick handles and looked heavy and sturdy. Overhead, fluorescent lights were buzzing and humming noisily, bathing the place in a sterile white light. CJ noticed that the lights looked as old as everything else in the Drodden Police Station. Every so often, the lights would rapidly flicker for a few seconds before stabilizing again.

“Come on over,” Otis said to the children. He walked over to a large, round desk where an older-looking woman with dark hair and very thick glasses who was typing on an extremely outdated-looking computer. And as the area to either side of the desk became visible, CJ realized it as a waiting area — with chairs and magazines, looking not unlike a bigger version of the waiting room at Dr. Laddow’s office. CJ’s throat clenched, thinking of Dr. Laddow — and Mickey Laddow. She saw familiar faces, and took a mental picture. And CJ’s father, Kevin Sweet, was seated there, looking anxious and ashen. In the chairs opposite her father were seated Stuart and Kelli Redwing, Jay’s parents. As CJ first caught sight of them, Stuart was lifting his wife’s hair and whispering urgently into her ear, his face looking stern. Over in the corner of the waiting room was Hilda Leek, Rick’s grandmother. She was looking over past the desk, toward the direction of a painting of a man and a woman in a wheat field on the hall’s opposite side. CJ noticed that Hilda’s eyes were wet and her face was red.

“Oh, Jesus!” cried Mrs. Redwing as they came around the corner. “My sweet baby!” She leapt up from Stuart’s side and knelt down to wrap her arms tight around Jay, who blinked wide-eyed … like it somehow surprised him. “My sweet baby!” Kelli said, her face pressed against Jay’s right shoulder. “Thank God you’re alive!”

CJ felt like Jay’s parents were always putting on a show like that, when there were enough people around them. But her father wasn’t like that. Instead, he did exactly what she’d predicted — and hoped — that he would do. He simply stood up, two steps toward her and reached out to rest both of his hands on CJ’s shoulders. Then, he squeezed gently. CJ reached up and hugged him. He didn’t engulf her into any kind of performance for others’ benefit; there was no wailing, nor did he call her an angel or anything like that. They just hugged, for a long moment. She could feel his chest heaving a little every so often. CJ wanted to just shut her eyes and block out everything else except her dad until she felt better. But she kept herself awake and aware — even in the embrace. Then, when they stepped away from each other in mutuality, she started looking toward the others in the room. She was taking mental notes, even as she felt the relief of her father’s presence. She glanced up toward her father; she noticed that he, too, was taking little moments to watch the others every so often.

Ms. Leek’s reaction was a lot closer to the Redwings’ — a loud shriek followed by a lot of hugging and tears. “You look awful,” Ms. Leek cried. “You look so sick. It’s all right now. It’ll be all right. We’re all here now. We’ll make everything all right.” She buried her face against Rick’s shoulder the way Mrs. Redwing had. Rick, however, for his part, didn’t look as surprised as Jay had a moment ago.

CJ hated it when adults told children things would be all right. They didn’t know. They had no way of knowing. They could try to make things better, but better wasn’t always all right. She felt a sort of pride in thinking how she couldn’t remember a single time her father had told her he’d fix everything, or make everything all right. Her father had always told her to adhere to the facts, and the truth. But she also understood why the other adults were consoling their children like that, and she felt sympathy. She understood why some children even needed that kind of consolation — the fast, easy kind that wasn’t always necessarily true. But that kind of easy comfort wasn’t something CJ was interested in. She felt like it dulled her awareness of what was really going on. She was pretty sure her father felt the same way.

Otis waved his arms, trying to get everyone’s attention. “Okay – so – just in case anyone’s worried … nobody here is in trouble. We just kind of want — …. ”

Otis was interrupted at that moment, by a loud crackling sound. A few seconds after it started, the crackling changed into a loud buzzing noise, and then there was a loud snap. And then, all the electrical power on the second floor of the police station went out.

Be First to Comment